The debate is dividing the world in meta-optimists and meta-critics. Whatever answer the metaverse wants to provide to humanity, the discriminating factor for its success will be the question it answers. And the managerial challenge an historic turning point.

Lucio Lamberti, Professor of Marketing and Scientific Director of the Metaverse Marketing Lab, School of Management Politecnico di Milano

In recent months, the discussion on the metaverse as a technological, economic and social phenomenon has been experiencing a time of turmoil and debate. On one side, the advocates of a metaverse-centric vision foresee a future in which we will wear virtual reality headsets for several hours a day, living a kind of parallel experience in one or more virtual universes. On the other, those who observe the numbers that metaverse platforms such as The Sandbox and Decentraland are moving (a few hundred or thousand individual users each month, after a period of enormous growth even in the virtual land prices in the last two years) already predict the third extended reality bubble after Second Life and following the announcement of the launch of Google Glass.

As often happens in this kind of debate, both positions probably contain elements of truth and elements more open to question. It is indeed true that a metaverse economy (and its finance) exists: in 2021 JPMorgan estimated a turnover of 54 billion dollars spent on direct-to-avatar purchases (skins, experiences and similar) bought on gaming platforms such as Roblox or Fortnite by a population of nearly half a billion regular users. Last year not only did Facebook change its name to Meta, going ‘all-in’ with regards to the future of the Metaverse, but Microsoft made a bid for Activision Blizzard for around 69 billion dollars, with the declared intention of strengthening its design skills in 3D digital experiences in view of the development of this market, and a total of 80 billion dollars was invested in Web 3.0 and Metaverse companies.

Numerous businesses and industrial groups are buying companies that design video games and hiring 3D programmers to develop their ability to offer immersive experiences to their clients, but also to their future talent (indeed, one of the most successful areas of application of the 3D web has been precisely recruiting and job interviews). On the other hand, in addition to the aforementioned problems in penetrating virtual second life platforms, there is also evident turbulence typical of pure financial speculation in the world of NFTs, virtual real estate and cryptocurrencies and we are likely beginning to notice that the production of content for the immersive web is currently very challenging. The parallels that some feared between the development of social networks and the development of the metaverse are less obvious than they might seem: social platforms clearly experienced exponential and extremely rapid development thanks to a very limited cost of content creation, which has engendered a virtuous cycle of production and presence on the part of the users. In the case of the metaverse, the cost of content production is (at least for the moment) much higher. And the metaverse critics tend to emphasise the fact that the technology enablers behind the alleged paradigm shift are not themselves actually new (virtual reality has been an established field for at least 30 years) and that the previous attempts at mass diffusion of 3D technology failed (primarily films and TV).

In short, positions are conflicting, the hype is huge, as is the confusion, given that the definition of the metaverse itself, its differences from web 3.0, augmented reality and mixed reality (real and virtual) are somewhat fluid. Therefore, in order to analyse what this global interest could be, it’s worth taking a step back and sharing some thoughts on the 3D web and the immersive digital experiences as applied in our lives.

From a sociological perspective, we should examine if and to what extent there is the need for these applications. And the answer is that there are areas which could greatly benefit from them, such as education, which during the years of the pandemic saw an exponential increase in online learning, discovering the ground-breaking potential for breaking down access barriers, but also the limits in terms of experience if limited to the two-dimensionality of video conference systems. Or tourism, which could leverage immersiveness and digital copies of cities to promote preview experiences and post-visit follow-up, extending contact with visitors. Or in the B2B sphere, there is the opportunity to develop virtual words which, with the help of artificial intelligence, offer precise replications of real situations for the purpose of simulating actions (for example surgeries or particularly delicate maintenance operations) and assessing the results, or even seeing them replicated in real life by robots or connected devices. Or even in an organisational or R&D environment for the creation of knowledge-sharing spaces that are more user-friendly and ‘welcoming’, in order to maximise creativity, production or interactivity among participants.

But the fact that these needs exist is not reason enough for the solutions developed to actually have real application. In order for this to happen, the experiences of individuals in these situations must be able to achieve better results than the physical or two-dimensional digital alternatives, in terms of efficiency, effectiveness, pleasure, safety, etc. On this front too, the answers are still emerging; and, whilst it is true that a large body of literature suggests that immersion could foster the development of in-the-zone experiences – that is, experiences capable of maximising learning despite a perception of effortlessness – it is equally true that this potential effect strongly depends on the ways in which the experiences themselves are created and proposed.

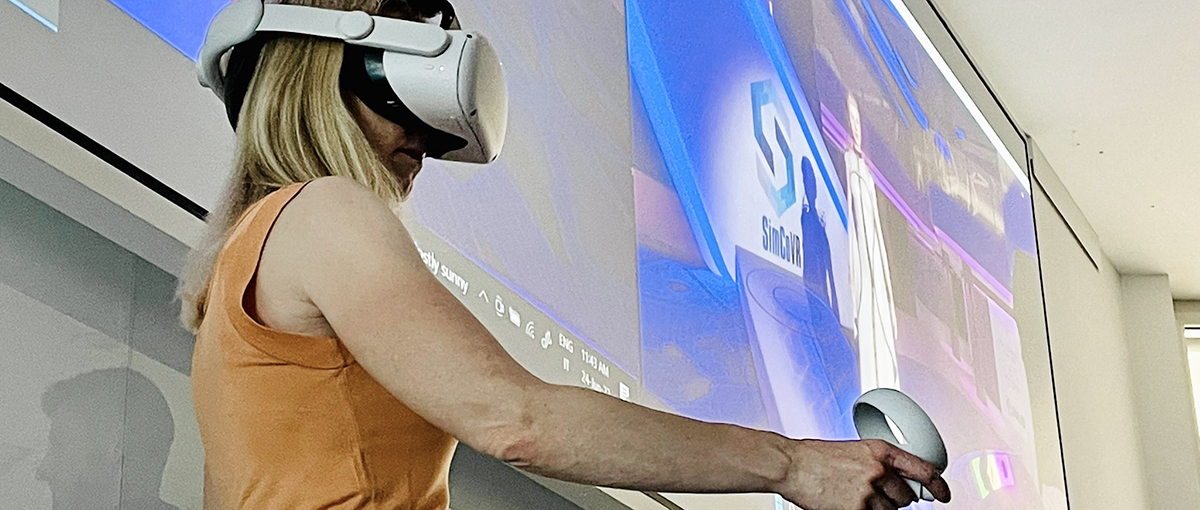

For this reason – with regards to marketing applications – the School of Management at the Politecnico di Milano has launched an initiative called Metaverse Marketing Lab which seeks to study two elements: on one hand, the state of art on offer in this type of experience in marketing on a national and international level, in order to understand what is actually available and the results achieved; on the other, the study of users’ reactions to these experiences including through applied neuroscience expertise in the Physiology, Emotion and Experience Lab (PhEEL), which analyses the user experience of individuals through objective measurement of biological signals.

In conclusion, although still in the very early stages of development of the topic, there are some considerations that can be advanced.

Firstly, there is much debate on the subject of platforms and possible metaverses and, while many companies draw on centralised and decentralised platforms to tap into the already existing audiences, many others develop their own metaverse.

It is at least desirable that, in the long run, the issue of interoperability among these worlds – at least in terms of technology enablers and communication protocols – take centre stage.

Secondly, while it has been stated that there are various cases of potential need, this is not sufficient to identify a profile of usefulness of the solutions already developed; this means that the success and, even before that, the very reason for the existence of a solution developed by an organisation in the metaverse depends on the type and relevance of the problem it aims to solve. Very often, technology enablers lead economic agents to develop solutions without specifying the problem they are solving, and this has always been the main cause of failure in innovation initiatives.

Finally, focusing on marketing applications, it should be noted that the persistence of a brand’s presence in a metaverse, whatever it may be, requires an even greater capacity than with web 1.0 and web 2.0 for continuous content creation. It is no coincidence that the companies that are riding the wave of the metaverse with consistency and continuity are often content creation and entertainment companies with initiatives linked to the launch of new films or series. Businesses are structurally geared to the creation of products and services, and not to the creation of content, and this is why they have delegated this activity over time to an ever-growing system of agencies and third parties.

Most likely, one of the great challenges of the metaverse for businesses will be the ability to develop in-house content creation processes, and this would be to all effects a revolution in business models, changing the system of relationships with the market, key in-house assets and resources, and the system of key partners for the development of the value proposition.