Whatever the post-Covid future, the new normal will require a fundamental change in the leadership of companies. What kind of mentality should leaders have to do business and innovation in a world that will be completely different? In a period in which the temptation will be to be increasingly competitive due to the scarce resources available, learning to share may be the only strategy that can guarantee survival.

Roberto Verganti, Professor of Leadership and Innovation

School of Management Politecnico di Milano, Stockholm School of Economics, Harvard Business School

Many executives wonder about a fundamental question: how to get ready for the “new normal”? How markets will look like when the main wave(s) of the Covid-19 pandemic will recede? How to redesign products, services and operations to address potential structural shifts?

The start line to rethink how we operate is getting close. Those who get ready now, will start with the right foot. Those who wait, will look like dinosaurs from an old era (though that era was just a few months earlier).

Magazines, futurists, consultants, organizations. Everyone is trying to picture how the scenario will look like as people open up their doors to a new normal life. And everyone agrees on two things: first, the world will look different than before. Second, this transformation will not be temporary. Even when Covid-19 will be fully defeated (and hopefully it will be), our attitude towards socialization, our openness towards the world, our need for health (and anxiety for new infections), will be radically different, for the bad, but also for the good.

Yet, as we move closer and try to get into the details of how life will look like, how markets and operations will work, the real challenge emerges: the phenomenon we are facing is so unprecedented, disproportioned, and swift that capturing the essence of what will happen is implausible. A simple figure to explain the rapidity and magnitude of the discontinuity: in March 2020 more than 7 million Americans have filed for jobless claims per week. This is about tenfold compared to what happened during the financial crisis in 2008. So, regardless to the intelligence and effort we invest to predict what will happen, we need to admit that the answer to the question “how the world will look like?” is: no one really knows. This is a bit of a dismay for the classic way we picture leaders (and experts), who are supposedly those who always know. Yet, in this context, “pretending to know” is the most dramatic mistake we could do.

Amy Edmondson illustrates in her book The Fearless Organization that when a person admits that she does not know, then she opens the doors to learning. To understand how to do business in the new normal the mindset we need therefore is not to guess how it will be, but to get prepared to learn.

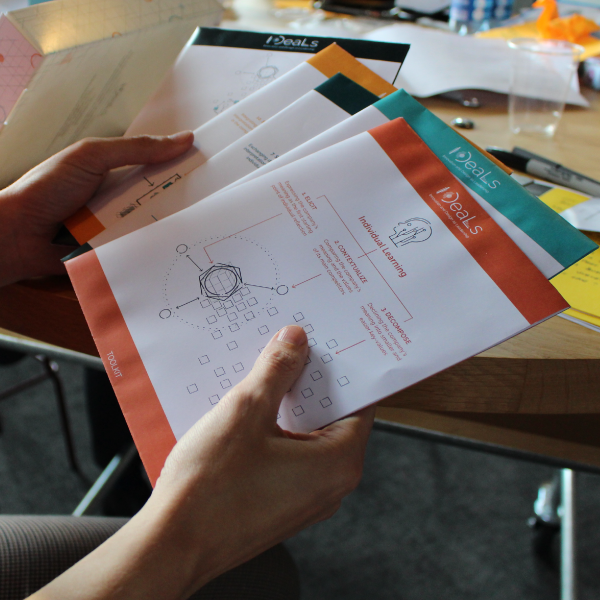

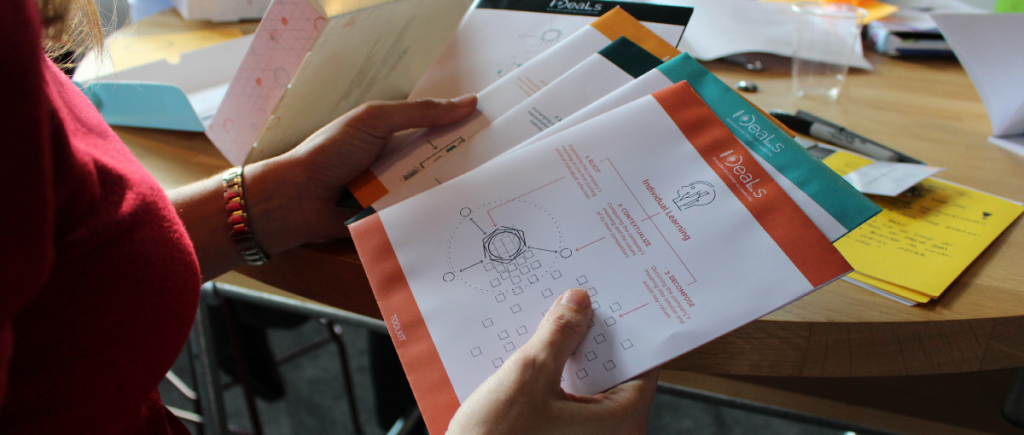

How? Being the context completely new, we cannot rely on past experience. We will need to learn “on the fly” through continuous experiments and adaptation. There are two ways to experiment and learn: by competing (learning by trying) or by collaborating (learning by sharing).

Learn by Trying. This the classic way of learning. The purpose here is to learn by yourself in order to beat your competitors. In this approach, organizations compete by conducting different experiments. Each organization tries its own ideas, fail, learn, adjusts the direction, and iterate. As companies aim to disrupt their competitors, they do not share their findings and insights with other organizations, nor the data that fuel the learning. This implies that every time an organization has an idea, it needs to explore it by only relying on its own resources.

Learn by Sharing. In this approach organizations conduct again different experiments. They generate their own ideas and iterate. However, they share the data and findings of their experiments. Why? Because this way they can leverage the trials of other players. If an idea has already been tested, and fails, others can avoid this unpromising path and focus on other options. And if the idea succeeds, others can build on top of it, instead of having everyone starting from scratch. Of course, this path reduces distances among competitors. Disruptions with one big winner and many losers are less likely to happen. But the advantage, however, is that that this approach requires less resources (individual and collective) and less time to get to good solutions. This increase in overall productivity and speed facilitates the growth of demand for solutions, which fuels returns to each player. In other words, this mechanism of learning replicates the mechanisms of the prisoner’s dilemma: cooperation between players leads to higher yields than what players would earn if they would maximize their own individual returns.

Learn by Trying is the kind of learning that has been prized in the past decade by many innovation thinkers and epitomized by the motto “fail often to succeed sooner”. It worked as long as the environment changed rapidly but in a linear fashion, so that learning from one experiment could be applied to the next one without the context being changed dramatically meanwhile. The change we are facing now with Covid-19 is however discontinuous and unprecedented. If in this context everyone conducts experiment by itself, each player has not sufficient time to explore this uncharted space of solution and then iterate before the context evolves again.

To innovate in the new normal we need to learn by sharing. This strategy is the only one that can guarantee sufficient scope, speed and productivity of the experiments. In fact, data sharing enables a larger community of players to participate to the experiments, from a larger variety of settings. And the sharing of findings enables to avoid unproductive trials.

Learning by sharing is already practiced in scientific research connected to Covid-19. Foer example, PostEra, a start-up based in Santa Clara, CA, and London, UK, is coordinating a massive collaborative project, Covid Moonshot to rapidly develop effective and easy-to-make anti-Covid drugs. The focus of the project is to design inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (the enzyme that enables the virus to replicate). The project leverages data shared by experiments conducted in a synchrotron radiation facility, Diamond Light Source, that has identified 80 fragments of molecules that might attach to the protease. A community of scientists and manufacturers use those data to design compound inhibitors, which are submitted through the PostEra website. The start-up then runs machine learning algorithms in the background to check for duplications and prioritize candidates for testing. More than 3’600 molecules designs have been submitted with only 32 duplications in the designs.

Shared learning is getting its way also in ordinary business not connected to Covid-19. Microsoft has recently launched an Open Data Campaign. The Open Data movement promotes the sharing of data, similarly to what Open Source does for sharing of software code. Microsoft will develop 20 new collaborations built around shared data by 2022, including, for example, publishing a Microsoft’s dataset around broadband usage in the US.

Note that shared learning does not imply that different players collaborate on the same idea or solution, like in consortia. On the contrary, organizations explore different ideas and experiments. This enables to explore the entire space of solutions. What is shared, instead, are the data that feed the experiments, and/or the insights and findings they generate.

Learning by sharing is built on a will to cooperate. Which is not easy to achieve. Especially in a period of scarce resources. The temptation is to look inward, and behave even more competitively, to secure the few things left, instead of focusing, collaboratively, on building more. What kind of culture and mindset will innovation leaders need to promote learning by sharing in their own organizations?

Whatever the future will look like, the new normal will require a fundamental change in the way we create innovation and lead our organizations. Whereas the innovation mantra of the pre-Covid era was to “disrupt competitors”, this is not really the moment to disrupt. This is rather the moment to collectively re-build a new economy and a new world. The real heroes, in business and society, will not be the disruptors, but those catalysts who will foster a cooperative mindset. Which, in innovation, it means to share data and learnings from the experiments everyone conducts. Organizations will need to try different competing ideas, but they will also benefit from sharing insights, in order to avoid unpromising avenues, improve collective productivity, and rapidly build a new society. Covid-19 is the moment of truth for leaders: where they can prove their authentic orientation to lead organizations around purpose and meaning.