Conversation with Giuliano Noci

Professor of Strategy and Marketing and Vice Rector of the Chinese Campus of Politecnico di Milano

The Joint School of Design and Innovation Centre in Xi’an, inaugurated in 2019 in collaboration with Xi’an Jiaotong University (XJTU), is the first physical campus of the Politecnico di Milano outside Italy. It is an unconventional choice for an Italian university. How did you manage to finalize this project?

Our relationship with XJTU began 12 years ago thanks to a Chinese student who had the opportunity to see the quality of our doctoral programmes, in particular the doctorate in electrical engineering under Professor Sergio Pignari. It was he who, working hard for many years and taking many trips, began to build this bridge between us and China, until he developed this strategic partnership.

We first initiated various exchanges and combined Laurea courses. The idea of having a physical presence on the new XJTU campus then arose and was realized with the construction of a building designed by architects at the Politecnico di Milano (Remo Dorigati and Pierluigi Salvadeo with studio wok, Chiara Dorigati, Francesco Fuoco), which we will fill with people very soon thanks to the numerous projects we have incubating.

What effects did the pandemic have on this project and how did you reorganize yourselves?

The pandemic did not stop the projects; it just led to a partial review of the objectives we had set.

The idea was to start in September of this year with a joint Laurea (Bachelor of Science) course in architecture with our instructors physically present in China. Since this is not possible, we have temporarily moved educational activities online, drawing on the expertise that the Politecnico has gained in recent years.

Secondly, we moved forward an important agreement regarding MBAs made between the MIP — our Graduate School of Business — and the XJTU School of Management, which is one of the most prestigious in the country.

Finally, on the new campus we would like to create a new Joint School accredited by the Chinese Ministry of Education.

This would therefore result in going beyond the goal of having a physical presence: building a true joint university venture abroad. In recent weeks we have been developing the concept of a new Bachelor of Engineering in Industrial Product Design involving various Schools at the Politecnico di Milano (Design, Management, Mechanical Engineering, Information and Communication Technology). If the project wins the call from the Chinese Ministry of Education, it would, in fact, be the first pilot course at the new school, with unique distinctive features, above all interdisciplinarity.

Interdisciplinarity is essential in processes of innovation, about which Italy has certainly much to say. And China is strongly dedicated to this front, as shown in the Made in China 2025 plan that was launched recently.

So, education, but not only that: a university partnership that aims to be relevant for the country system?

Certainly. Our goal is also to support strategies for the international and technological development of our businesses. In this sense, Xi’an is one of the most important industrial districts in China, for the automotive and electrical industries in particular, and it is also a very important cluster in the ICT sector (Alibaba and Huawei have very important research centres there).

This is why we plan to have laboratories where we intend to carry out research together with Italian and Chinese companies. The Chinese market is complex but extremely attractive for our companies, and we can support them in their entrance into the market.

Let’s talk about students. The added value of international exchange during a course of university studies is indisputable, but how do students respond to the opportunity for a combined Laurea of this type?

The ambition of the Joint School is to go global. We intend to attract international students from around the world. But we also want to support growth and experience for our researchers and instructors, given that this is an opportunity for them to develop under multiple points of view.

Students’ reactions up to now have been enthusiastic. Faced with legitimate initial scepticism in studying on a continent that is so different from ours, Italian students have always had extraordinary appreciation for this cultural exchange. They are won over by the energy and dynamics characteristic of any Chinese university.

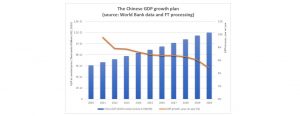

They realize the importance of interacting in an area with one of the highest rates of economic growth in the world, characterized by great encouragement and strong investments in digital technologies and artificial intelligence.

A partnership developed, as you said, based on continual work of visits to the host country. Now this specific historical situation imposes new forms of interconnection around the world.

What scenarios do you foresee in view of this? How do the distances bring us together or modify some means of interaction between us and China?

The topic of Hybrid Learning will further accelerate relations between the Politecnico di Milano and China. In recent months, when the number of trips has reduced to zero, we have actually interacted more frequently than before and have increased the level of objectives and results obtained. In this direction, with regard to both research and university/postgraduate teaching, previously little-explored perspectives are opening.

In China, during the period of quarantine due to COVID, a good 180 million students studied entirely online. For us, it is now natural to expand our educational programme beyond the physical presence of Chinese students, when students do not want to move. Applying the reasoning of Hybrid Learning (with in-person and remote lectures) also opens participation in new courses of study to Italian students who do not want to move to China, for example.

Paradoxically, at a time when physical connection was not possible, cognitive and relational interconnection was more frequent because on both sides we discovered the possibility of working with a never-before-imagined frequency of interaction precluded only by our sensory system.

For example, with Tsinghua University in Beijing — the most important university in China, which has a joint campus in Milan at our Politecnico — we are now launching three large educational projects involving the MIP Graduate School of Business (in addition to other university departments) which were developed in just six months. To obtain similar results in the past, four/five years of continuous trips would have been necessary.

This naturally does not mean diminishing the importance of physical contact and campus life.

It just implies new roads that are worth travelling.

One last question about the educational approach in Chinese management schools. Is the material taught evolving in a way more inclined to collaboration with the West, or are the two models radicalizing into different positions?

The perception I have always had about China is that there was curiosity about Western managerial models. What was interesting, however, were especially topics tied to managing innovation.

The approaches move in opposite directions. China is aware of the power of its economic system and is therefore self-referential, even in its means of management.

This, however, does not preclude different opportunities for us — as the Politecnico and as Italians — particularly for two reasons.

The first is the very high number of Chinese students that want to study abroad and who will move to Europe in significant numbers (and also to Italy, we hope).

The second is that Italy is very attractive for our capacity to both develop a system of small and medium-sized companies, and create luxury brands. This is a great reputation, on the level not only of design, but also of marketing.

As a result, our country and our management schools are decidedly interesting.

If you had to briefly give 3 keywords for the future of the Xi’an project in the short term, what would they be?

Consolidating the Joint School to favour paths of growth for young talent at the Politecnico.

Opening a couple of laboratories with companies: one in the automotive industry and the other might be exporting the Polifactory format to Xi’an.

Creation of a start-up incubator with the related establishment of a venture capital fund.