The Covid-19 pandemic is the harbinger of unpredictable and unprecedented scenarios. But the adaptability of industrial supply chains and a proactive approach can make the difference.

Paolo Trucco, Professor of Industrial Risk Management

In its Global Risk Report 2018, the World Economic Forum had already given a clear warning sign. “Humanity has become remarkably adept at understanding how to mitigate conventional risks that can be relatively easily isolated and managed with standard risk management approaches. But we are much less competent when it comes to dealing with complex risks in the interconnected systems that underpin our world, such as organizations, economies, societies and the environment. There are signs of strain in many of these systems: our accelerating pace of change is testing the absorptive capacities of institutions, communities and individuals. When risk cascades through a complex system, the danger is not of incremental damage but of “runaway collapse” or an abrupt transition to a new, suboptimal status quo.”

The picture that has been emerging in recent weeks as a result of the coronavirus pandemic has all the characteristics of being a systemic risk, which will have long-lasting effects over time and from which we must expect radical and structural transformations of society as well as the global economic system. From an industrial standpoint, much will depend on the ability of businesses to understand how the global scenario is evolving and to adopt a proactive and adaptive approach, both in the short run, to respond effectively to the impact on operations, and in the long term, to adjust their business models to the new context.

High-Tech and Automotive: the global supply chains most affected to date

In the province of Hubei alone, where activities are still broadly at a standstill, around two million cars are produced every year, second by volume only to the area of Guangdong. In January and February 2020, over 60% of Chinese assembly plants were shut down or in some way affected by the spread of the crisis. Global brands such as General Motors, PSA, Renault and Honda have their own plants or joint ventures in the region to serve the entire Asian market. All these plants have suffered production shutdowns for at least 12 days and still operate under limited capacity.

China is also a major exporter of motor vehicle components (USD 33.5 billion in 2019), especially to the US, EU and Japan. Producers in the province of Hubei are typically Tier 2 suppliers, which supply Tier 1 suppliers located in other parts of China; the latter, in turn, ship their products through the east coast ports to reach the western markets.

The entire global car industry, which adopts very aggressive JIT models and thus keeps very low inventories, has suffered, or will suffer, production shutdowns due to the lack of critical components: FCA has had to shut down some of its European plants; and under current conditions, GM will only be able to operate in the US until the end of March.

Lastly, a third element is of paramount importance in understanding the impact that the Chinese coronavirus epidemic will have on the automotive sector, namely the significance of that market for the financial stability and profitability of many American and European brands. In 2019, GM sold more vehicles in China than in the United States and the Volkswagen’s joint ventures in China accounted for over 26% of the Group’s EBIT in 2018.

The global electronics industry is also heavily dependent on Chinese production in many segments of the whole supply chain. Critical materials such as rare-earth elements (REEs) are extracted in great quantities in Guangxi and the whole sector has already experienced, in 2010, the devastating effects on production volumes and costs of a drastic contraction in Chinese exports of these materials. There are also important producers of chips and printed circuit boards in the province of Hubei, but in this case the highly-automated processes have mitigated the impact, leading to a rapid recovery to normal operations. Final assembly companies, such as Foxconn, are predominantly located in the areas of Guangdong and Shanghai, or in other neighbouring towns. Assembly phases are typically labour-intensive and, for this reason, these companies have suffered the greatest constraints. This has had a significant impact on market leaders such as Apple or Hewlett Packard, which in recent years, have concentrated a large part of their supply base in China.

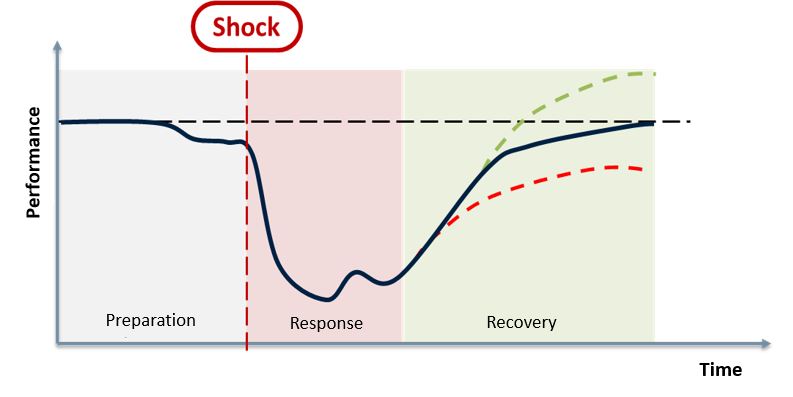

Black Swan and industrial Darwinism: those who change win, not those who resist

The global crisis that we are starting to tackle will make it even more obvious that in a rapidly- changing and highly uncertain world, the adaptability of organisations and industrial supply chains is an key factor for success. Resilient supply chains are characterised by their ability to sense weak signals of emerging pressures or shocks, to prepare for the unexpected and to respond rapidly and in an adaptive manner to crisis situations, by reconfiguring their processes and operating models. It is by adopting a similar proactive, rather than reactive, approach that resilient organisations can also turn threats into opportunities, performing better than their direct competitors, or adopting innovative solutions that structurally change the competitive landscape in the aftermath of a crisis.

In the last decade, both the automotive and the high-tech industries have faced big disruptions that are very similar to the current one and have learned important lessons. Undoubtedly, the most significant event is the triple disaster that hit Japan in March 2011, which saw a combination of the biggest earthquake in the last 140 years of the country’s history, a devastating tsunami and the resulting nuclear accident. DELL was one of the most exposed high-tech giants at that time, as it had a large number of its components sub-suppliers located in the most affected area, which, in turn, supplied the assembly plants in Korea and Thailand. Thanks to its MTO (make-to-order) operating model, fed purely by on-line sales channels and supported by very strong relationships with suppliers, DELL was able to successfully manage the crisis via three broad actions: dynamic management of supply and shift of demand to feasible product configurations based on available parts; on-site coordination of the emergency thanks to technicians and procurement managers physically located in Korea and Thailand; and technical and operational support to suppliers, thus ensuring maximum visibility and coordination at all levels of the supply chain. Its direct competitors were not able to do the same, suffering losses both in turnover in the short term and in major market shares once the crisis was over.

The automotive sector was also substantially affected by the so-called “triple disaster”, which brought the Japanese economy to its knees. When, some months later, the rainy season brought huge flooding and devastation in Thailand, lasting from July 2011 to January 2012, Nissan Motors also found itself facing a second severe emergency just few months later. While the three major Japanese manufacturers recorded losses of over EUR 300 million in operating profit, Nissan’s sales hit an all-time high in fiscal year 2011, while profit grew year-on-year.

How can we explain such a difference in results in the same operating and market conditions? At that juncture, Nissan certainly proved the value of its corporate motto: “The power comes from inside”. In the few months from March to July, Nissan was able to put into action lessons learned from the disaster in Japan and exploited them fully to tackle the new disaster: extensive and consistent implementation of a business community management (BCM) system, coordinated by a Global Disaster Control Headquarters; review of sourcing strategies and redesign of the supply base, based on a multi-level risk analysis; intensive exchange of information and coordination with suppliers and sub-suppliers; and review of production plans to take advantage of the production windows of suppliers granted by “rolling blackout” policies implemented by the Thai electricity operator.

While, on the one hand, the Chinese coronavirus epidemic cannot be categorised as a black swan, it is equally plausible that its transition into a global pandemic, as declared by the WHO in the first week of March, is the harbinger of unpredictable and unprecedented scenarios. For example, the extension of production shutdowns in north Italy in the wake of what has happened so far in the Lodi area would represent a hard blow to the entire European automotive sector.

What awaits us once the emergency is over: threats and opportunities

The Chinese government’s initial response to the spread of the virus, at both central and local level, was drastic: the complete closure of factories and companies and a substantial ban on movement by people. Now, when major progress is being made in containing the virus in various areas of the country, the central government has launched an aggressive “return to work” campaign. This includes financial support and medical supplies to companies that are resuming activity, as well as huge efforts to re-establish essential services. The local authorities are also acting synergistically, implementing differentiated actions specific to the conditions of different cities and provinces. Only the province of Hubei is still subject to major containment actions.

However, the recovering Chinese economy is significantly different from the pre-coronavirus economy: not only because many companies have not weathered the impact and have gone bankrupt, e.g. in the construction sector, but also, and most importantly, because in many sectors the coronavirus has led to drastic operational restructuring and business models innovations. One example that stands out is the substantial increase in capacity of the medical sector, which, from now on, will take the role of a global player in all respects. In the clothing and personal care sector, the mix of sales channels has changed dramatically. The shift on e-commerce B2C and B2B channels during the emergency period has permanently changed the structure of entire supply chains, with long-term effects that are only for the moment limited to China.

This is all happening while the rest of the advanced countries are preparing to face the peaks of contagion, which will strike Europe and the USA synchronously. Here the key question comes: what will happen when, in late spring, China will be the only industrialised country with a fully recovered and transformed industrial capacity, and with a rapidly recovering domestic demand?

It is difficult to make predictions either on a global or local scale. What is very likely, though, is that in the West, as in China, the only supply chains that will survive and find new growth opportunities will be those that, after abandoning the “last Japanese” syndrome (i.e. resisting), will have been able to adapt to the changes, by innovating processes and business models.