Although it is not possible to predict the duration of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is essential not to be totally absorbed by the emergency and to start thinking about the most effective strategy to face the recovery phase.

Paolo Trucco, PhD, Centre for Risk and Resilience Management of Complex Systems

School of Management – Politecnico di Milano

The embers beneath the ash

With the pandemic still in full swing, and the numbers of new infections and deaths still rising, both in Italy and in other parts of Europe and the world, it seems inappropriate to think about what comes next, especially in terms of production. However, in order to live, a society, a community needs to be taken care of, it needs goods and services, which unfortunately cannot be guaranteed outside the market-economy model.

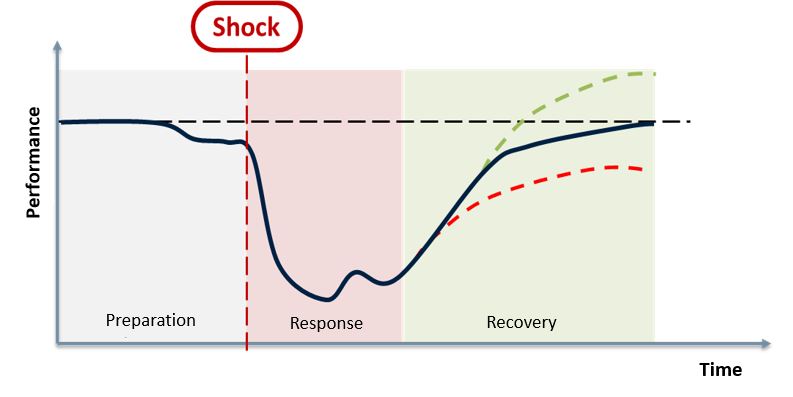

After two weeks of the government-decreed production block involving most industrial sectors, many companies have had to suspend every business activity or find temporary solutions to ensure minimal operational continuity. Even companies in the so-called essential or strategic industries are operating in emergency conditions and therefore with greatly reduced levels of performance. If we look at the typical profile of an operational disruption (Figure 1), we are currently all, for one reason or another, in the period of maximum impact. We do not know exactly how long it will last, nor how long we will be able to sustain it. However, if industry and Italian society as a whole wish to look to the future, it is important not to let ourselves be overcome by the gravity of this emergency and to start thinking about the most effective strategy for dealing with the recovery phase, so as to ensure it comes quickly and fully. The embers beneath the ash must be kept alive. We need to be prepared to seize the early signals of recovery and to turn every opportunity that may arise into value.

Figure 1. Time profile of an operational disruption with different recovery capacities.

What should we expect?

At the moment, no one is truly able to trace out how economic recovery will unfold. However, some fundamental elements seem to be clearly outlined:

- The recovery of supply and demand will take place at significantly different times in different parts of the world. Speed will also be different: for structural reasons, due to the severity and breadth of the pandemic, or due to the decisions made by local governments. In short, it will be a geographically asynchronous recovery.

- In every corner of the globe, national and supranational institutions will make a massive effort to stimulate the economy, but such measures may not be fully coordinated or consistent with each other. We will see a period of sub-optimal allocation of resources and not everyone will benefit in the same way.

- Due to its magnitude and degree of interdependence, crucial energy and transport infrastructure will most likely suffer most from the turbulence created by the two previous factors. As a result, global supply chains and energy-intensive industries may rebound with greater difficulty.

- The specific nature of the event has created both a supply shock (production stops) and a demand shock (rapid contraction in consumption and investments). The recovery phase, within the supply chain, will also be marked by the need to manage two opposing disturbances: a ripple effect, downstream, as a result of prolonged limited supplies, and a bullwhip effect, upstream, as a result of a recovering yet still highly uncertain and volatile demand.

Be ready at the (re)starting blocks

In a previous article on the impact of COVID-19 on global supply chains (Coronavirus is the acid test of global supply chains’ resilience), we already described the fundamental characteristics of resilient supply chains: the ability to sense weak signals of emerging pressures or shocks, to prepare for the unexpected and to respond rapidly and in an adaptive manner to crisis situations, by reconfiguring processes and operating models. Looking now more in depth at how to manage the recovery phase in specific contexts, we can identify three elements of resilience that we believe will play a key role:

- Visibility. The recovery phase can only hope to be successful by achieving end-to-end supply chain visibility, both as regards the operational capacity of suppliers and sub-suppliers and the dynamics of demand, in terms of geographical redistribution and sales channels. Unlike in normal conditions, the magnitude and mode of response to emerging demand will have to be planned according to the actual capacity of the supply chain, until a new state of structural equilibrium is reached.

- Collaboration. During a turbulent emergency, transparent, stable relations are far more important than tactical behaviour. Those who have been able to build collaborative relationships with their suppliers and distributors will find themselves in a position of greater advantage. The need to replace suppliers who have been unable to overcome the crisis can turn into an opportunity to strengthen relations with more dynamic, crucial suppliers.

- Multichannel distribution. With volatile, rapidly changing demand, the opportunity to use multiple sales and supply channels will allow companies to recover faster in the short term and, in all likelihood, gain new market shares in the medium term.

Actions and tools to implement a resilient strategy

Below is a list of practical, albeit incomplete, actions that may help to manage rationally both the present situation, for those first companies allowed to resume operations, and the time when production resumes universally:

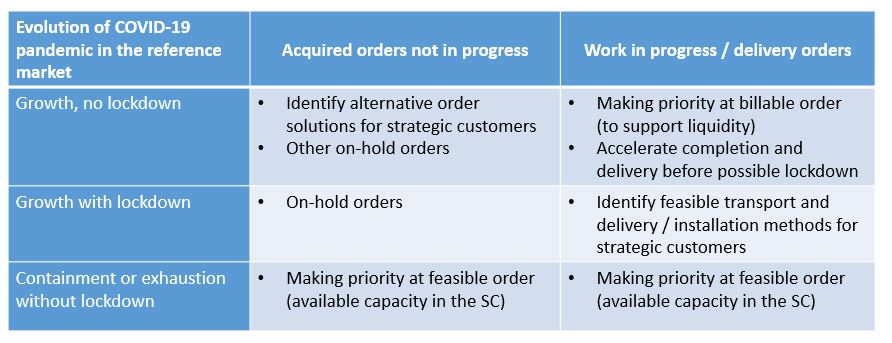

- Continuously monitor the evolution of the pandemic and of the measures implemented by governments in the most relevant markets (Figure 2);

- Segment acquired orders by degree of completion and customer reachability (status of pandemic control measures in the target country) and prioritise billable orders;

- Search for possible alternative configurations to execute high priority orders waiting to be processed;

- Reassess the priority of orders on a daily basis with a 1-2 week (rolling) visibility;

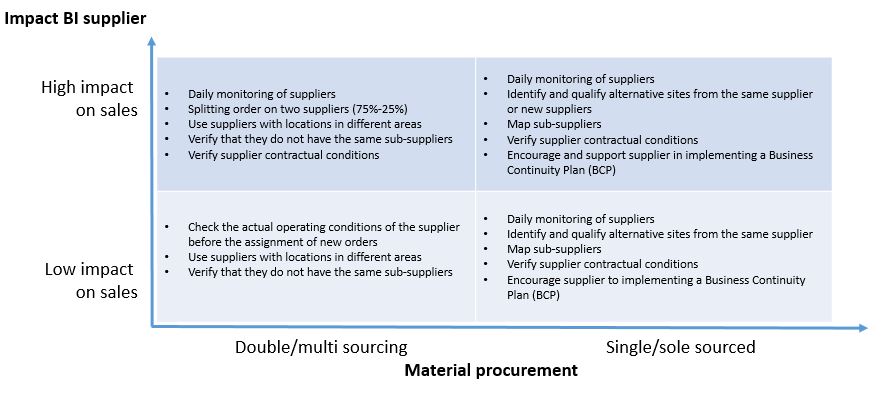

- Map the status of crucial suppliers (i.e. those having the greatest impact on priority orders) by drawing up a questionnaire to verify business continuity conditions (include questions requesting information on the business continuity of crucial sub-suppliers).

- Cross-check the business continuity assessment of suppliers (Figure 3) against the markets-orders table to identify feasible orders;

- Agree operational continuity plans and production capacity allocation priorities with crucial suppliers and re-schedule delivery times based on new order priorities;

- Evaluate alternative options for crucial vendors on complete lockdown;

Figure 2. Example of a market-order segmentation table based on the stages of evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic

Figure 3. Example of a table to manage the risk of supplier Business Interruption (BI)

It is no wonder that the speed with which we have been hit by the pandemic and the continuing uncertainty about how and when it will be managed by the authorities has left many feeling confused and disconcerted. However, now is the time to strengthen our evaluations and actions, leveraging on in-house skills and capabilities. It is never too late to pick ourselves up. It is never too early to prepare for what lies ahead.